Shanadithits Burial Shroud

photo courtesy of The Rooms. Installation shot of eltu’n klaman mukwite’ten | making to remember, 02024, curated by Emily Critch.

Artist Statement

Even though it’s dark and heavy and personal, I feel lucky to have learned the history of the Beothuk in grade school. I can’t remember to which teacher in my youth that I’m grateful, but it was only as an adult that I learned not everyone in canada learned the history, importance and grievous colonial destruction of Indigenous people in our respective territories.

I am Mi’kmaq, Nlha7kápmx with some mixed settler ancestry too. I come from Katalisk, Ktaqmkuk or Codroy Valley, newfoundland & Labrador. I live in my home community, in one of my two Ancestral Territories and I was born and brought up here too. I don’t have any connection, lived experience, or contact to any of the places or Landscapes that my settler ancestors came from - Europe and across Scandinavia. My mother is Renee Samms who is Nlha7kápmx and Italian through her mother and Mi’kmaq and French, through her father; my father is called Gerry Samms and is Mi’kmaq and Welsh, through both of his parents. Like I said, I live in my home and one of my two Ancestral Territories, Katalisk, where there are Beothuk place names and where our ancestors live/have lived, for a very long time.

The story of the Beothuk and especially, Shanadithit, has stuck with me through time. I think of her a lot. She was here when they came, this is the place of early/first european colonial contact and she and her family were the front line; Shanadithit was one of the first MMIWG2S. I continue to develop as an Indigenous person within the current cultural climate of canada; my world view continues to deepen and widen; I am proud of my ancestry, my connection to Land and my place, my family and my hybrid Indigenous ways of knowing and being. As I walk through life my identity continues to develop in specific ways, but also broadly.

When Shanadithit died in a St. John’s hospital on June 6, 1829, she was buried in a cemetery in St. Johns without a death ceremony that was conducive and important to her as a Beothuk person with Beothuk cultural practices. Shanadithit was buried in a grave without acknowledgement of her as a Beothuk person and without her kin nearby. In making this shroud, my intention is to provide something for her spirit that she and her kin may have appreciated as culturally appropriate, something made with care and concern, a shroud made to hold, comfort, and carry, something beautiful. This work and the process to make it is to offer a gift to heal a historical wound. I hope it reaches them.

The old people here tell me: my old people were Beothuk too.

I want to repeat: Shanadithit was one of the first MMIWG2S. Ktaqmkuk is the place of first/early european colonial contact. The violent colonial project on Turtle Island began here, like a wave it made its effects across the continent. Colonialism unfolded from this very point and the medicine to repair and the stories to show the truths of here will unfold in a wave too.

photo courtesy of The Rooms. Installation shot of eltu’n klaman mukwite’ten | making to remember, 02024, curated by Emily Critch.

Technical Specs

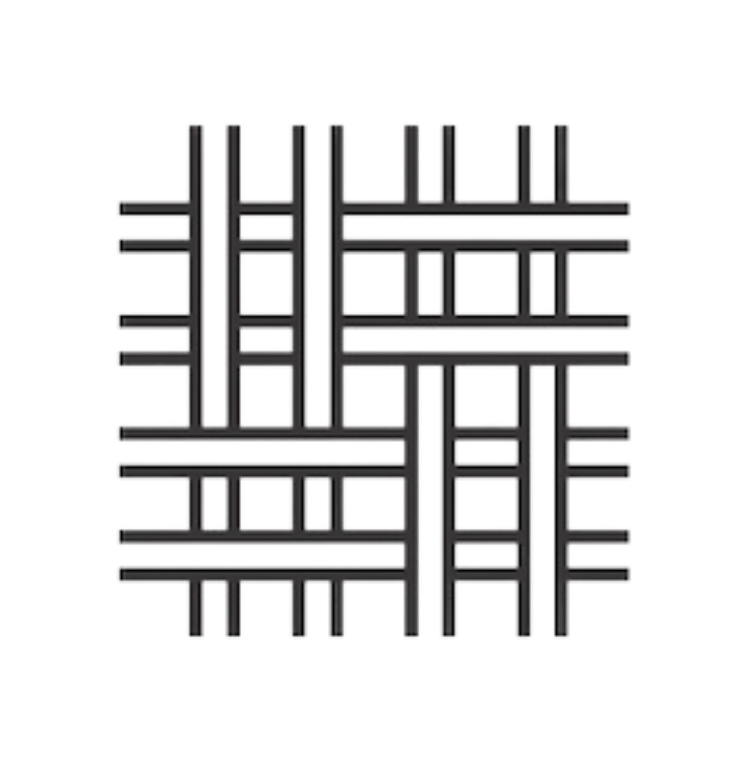

I began to work on this shroud in 02013 and finished it in August 02016; though on reflection, the research and thinking began a decade earlier. I produced work on a 10 shaft, countermarche loom; it’s double woven with 3 ply fingering weight wool yarn, 3 plies for 3 tenses: the past, present, and the future. The white yarn is undyed to reflect the colour of birch bark, the red yarn is dyed mainly with madder root that I grew. I planned the specific tone of red to reflect the colour of red ochre; madder root (Rubia tinctorum) is mainly and most often a red giving plant, but brewed at a steep temperature brings out the brown pigment present in the root. I tied up the treadles of the loom to allow the background white yarns to come to the surface of the cloth, above the red cloth layer, enabling me to create pockets which would eventually contain grave goods. In addition to being hand woven and plant dyed, I used other hand work too - beading, braiding and hand manipulated edging. The grave goods are: moose teeth, birds wings, a miniature canoe (carved by my partner, Ash Hall), smudge wrapped in moose leather and a lock of my own hair as elsewhen Shanadithit left a lock of her own hair.

Research sources for this project are varied: heritage.nf.ca (multiple pages), The Beothuk - Ingeborg Marshall and therooms.ca. In addition to these sources, I drew from memory and many lengthy conversations with my family and time with the Land I live with. During my research in the making of this work Janzens masters thesis illuminated the affirmation of the Peace & Friendship Treaty to me.

At the time of this original writing (02016), there has been news that Ottawa is actively supportive of the request to return the remains and grave goods of two Beothuk individuals to the land they belong to from a museum display in The National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.

Shanadithits Burial Shroud is in the collection of The Rooms provincial Art Gallery and Archive.